Neuroendocrine tumours (NET) are a group of diverse neoplasms arising from cells of neuroendocrine origin.

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) are rare tumours that start in neuroendocrine cells. You might also hear these tumours called neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) or neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs).

There are a number of different types of NETs. The type you have depends on the type of cell that the cancer started in.

Most NETs develop slowly over some years. They may not cause symptoms in the early stages. It’s not unusual for people to find that a NET has already spread to another part of the body when they are diagnosed.

The neuroendocrine system

The neuroendocrine system is made up of nerves and gland cells. It makes hormones and releases them into the bloodstream.

Neuro means nerve and endocrine refers to the cells of the endocrine system. The endocrine system is a network of glands and organs in the body that make hormones. It is also called the hormone system.

There are neuroendocrine cells in most organs of the body, including the:

- food pipe (oesophagus)

- stomach

- lungs

- small and large bowel

- pancreas

- liver

Neuroendocrine tumors are cancers that begin in specialized cells called neuroendocrine cells. Neuroendocrine cells have traits similar to those of nerve cells and hormone-producing cells.

Neuroendocrine tumors are rare and can occur anywhere in the body. Most neuroendocrine tumors occur in the lungs, appendix, small intestine, rectum and pancreas.

What neuroendocrine cells do

Neuroendocrine cells have different functions depending on where they are in the body. They control how our bodies work. This includes our growth and development, how we respond to changes such as stress, and many other things.

For example, neuroendocrine cells of the lung make hormones that control the flow of air and blood in the lungs. And neuroendocrine cells of the gut (digestive system) make hormones to control:

- the production of digestive juices

- the muscles that move food through the bowel

Where NETs start

NETs can start in different parts of the body. Like all cancers, NETs are named after the place they start growing. For example, a NET that starts in the lung is called a lung NET. This is the primary cancer. If the cancer spreads to another part of the body, it’s called secondary cancer.

Around 5 out of every 10 NETs (50%) start in the digestive system. This is also called the gastrointestinal (GI) system. It includes the:

- stomach

- small and large bowel

- pancreas

- back passage (rectum)

Around 2 out of every 10 NETs (20%) start in the lung. NETs can also start in other places such as the:

- food pipe (oesophagus)

- appendix

- skin

- prostate

- womb

- adrenal, parathyroid and pituitary glands

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are rare malignancies of the aerodigestive, genitourinary and integumentary systems. Their histologies vary from well-to-moderately differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) to poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) and their natural history has been described in several publications . Most studies are limited due to the small number of cases, inconsistent follow-up or retrospective nature but it is clear, however, that the incidence of NENs is increasing and that, at least for certain subtypes, survival might be improving.

NENs show a spectrum of behaviors and this makes their treatment challenging. Some exhibit an indolent, slow growth pattern, while others parallel the more aggressive, rapidly spreading tumors such as small cell lung cancer (SCLC); in between there are neoplasms of intermediate malignant potential. Research so far has identified stage, site of origin and differentiation, as well as proliferative indices (Ki-67, mitotic count) as important prognostic factors and multiple scores have been published, trying to predict survival in metastatic disease or recurrence after curative surgery. In general, well- differentiated tumors progress slowly and surveillance may be the best approach in some cases, whereas poorly differentiated neoplasms require urgent aggressive chemotherapy and are associated with markedly shorter survival. Tumors of small bowel origin tend to have a better prognosis compared to NENs originating in the pancreas. The effect of other factors such as age, race , resectability , performance status or even marital status has similarly been examined in several publications. Most medical decisions nowadays consider tumor of origin, staging, but also tumor differentiation and mitotic indices (values that have formed the basis of the current grading system ).

Recently, significant progress has been observed not only in our understanding of the biology and genetics of NET but also in the diagnosis and treatment.

Besides, newer classification and staging system have been adapted and guidelines published to help to establish a more standardised approach.

Although some series report slightly higher incidence in men compared to women, there appears no significant difference in terms of gender. The prevalence of the dis-

ease is however estimated to be much higher and ranks only second after colorectal cancers among gastrointestinal (GI) tumours . Although NETs may occur at any age, it is more common after the age of 50 . NETs may be associated with familial genetic neuroendocrine tumour syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes (MEN-1 and MEN-2), neurofibromatosis type 1, von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, tuberous sclerosis and Carney complex.

In patients with these syndromes, the age of diagnosis is 15–20 years lower than those with sporadic NETs.

NETs are usually slow-growing tumours. They can arise from many organs but commonly from GI tract and pancreas, lung, thymus and other endocrine organs.

NETs may synthesise and secrete peptides and/or amines. These secreted peptides/amines can be used as tumour markers, and they may lead to clinical symptoms.

NETs have some common histopathologic characteristics. They show similar immune reactivity to pan-neuroendocrine markers, chromogranin A and synaptophysin. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE), CD56 and CD57 are less specific markers; they can be used to identify poorly differentiated NETs. Immunohistochemical assessment of specific hormone expression is not routine in pathological evaluation, and positive immune reaction for hormone expression in the tumour tissue does not indicate that the tumour is functional. NETs usually express somatostatin receptors; therefore, somatostatin expression can be used both diagnostically and therapeutically. Somatostatin receptor imaging ( 111 In-DTPA-octreotide or preferably 68 Ga-DOTATATE) can be used for initial staging, follow-up and selecting patients for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy The role of newer PET tracers warrants further validation for routine clinical practice. Endoscopic evaluation of the patients with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, double- balloon enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy is critical according to the localization of the primary tumour and also in patients with primary unknown metastatic neuroendocrine tumour or carcinoma.

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of tumors secreting various bioamines and peptides arising from neuroendocrine cells in the endocrine and central nervous systems. NETs are responsible from approximately 0.5 % of all cancers.

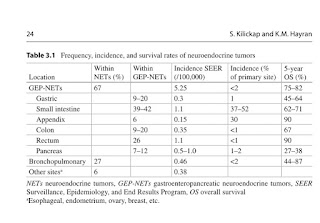

The incidence and prevalence of NETs have increased about fourfold for the last 30 years because of improvement in the diagnostic techniques. PNETs are more aggressive tumors compared with NETs originating in the other sites. Also, most of PNETs are malignant and tend to be in advanced stage at the time of diagnosis. Gastrointestinal tract is the most common location and is responsible for two-thirds of NETs. Small bowel is the most common primary site of GEP-NETs in the developed countries. PNETs are divided into nonfunctional and functional tumors which secrete hormones and peptides. In association with hormone and peptide secretion, functional endocrine tumors may be symptomatic. Bronchopulmonary system is the second most common location of NETs. These tumors consist of one-third of all NETs. Typical and atypical carcinoids of the lung tend to slowly grow. Most of nonfunctional lung carcinoids have been incidentally diagnosed. The prognosis of NETs associates with their location, functional status, differentiation, and initial stages. In advanced stage, the prognosis is poor. However, the overall survival of well-differentiated and localized NETs is longer. The best survival rates are observed in patients with NETs arising in the rectum and appendix. The 5-year survival rates of these tumors are excellent with over 90 %.

Cancerous or non cancerous

There is some debate among doctors about how NETs should be grouped and what they should be called. NETs develop in different parts of the body and behave in different ways. For example, some NETs grow slowly while others are faster growing.

All NETs are malignant (a cancer) by definition. Some NETs are diagnosed early and you might be able to have treatment to cure it.

More recently doctors have been calling them neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). This is an umbrella term for this group of disorders. Then depending on how slow or fast growing the cells are they are called either neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) or neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs).

NETs are usually slower growing and the cell changes are called well-differentiated. NECs tend to be faster growing and the cell changes are called poorly-differentiated.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment